Memorial Drive: A Daughter’s Memoir is by Natasha Trethewey and it was published in 2020. The quote in the title of this post is from William Faulkner, used by the author in her work. I finished the book last week, as was assigned in an integrated learning community (ILC) that I am teaching in this semester. The concept of an ILC is part of our general education program, and every student is required to complete it.

Each ILC consists of two courses where a topic is explored through two different academic or professional disciplines. There are ILCs on wellness, ancient wisdom, diversity, and all kinds of other topics, including the one I teach in, which is on trauma and adverse childhood experiences (ACEs). The course I teach is a standard Human Behavior in the Social Environment course with a heavy grounding in how the experiences of ACEs and other trauma have the potential to impact individual development throughout the lifespan. The second course, taught my colleague who is a faculty member in the English department, is a literature and writing course. At the same time students are learning about human development and adversity (and resilience and post traumatic growth) from a social work perspective, they are also reading memoirs and novels that have a connection to trauma and we are able to apply the concepts we are learning in the social work class to the experience of the characters in each book.

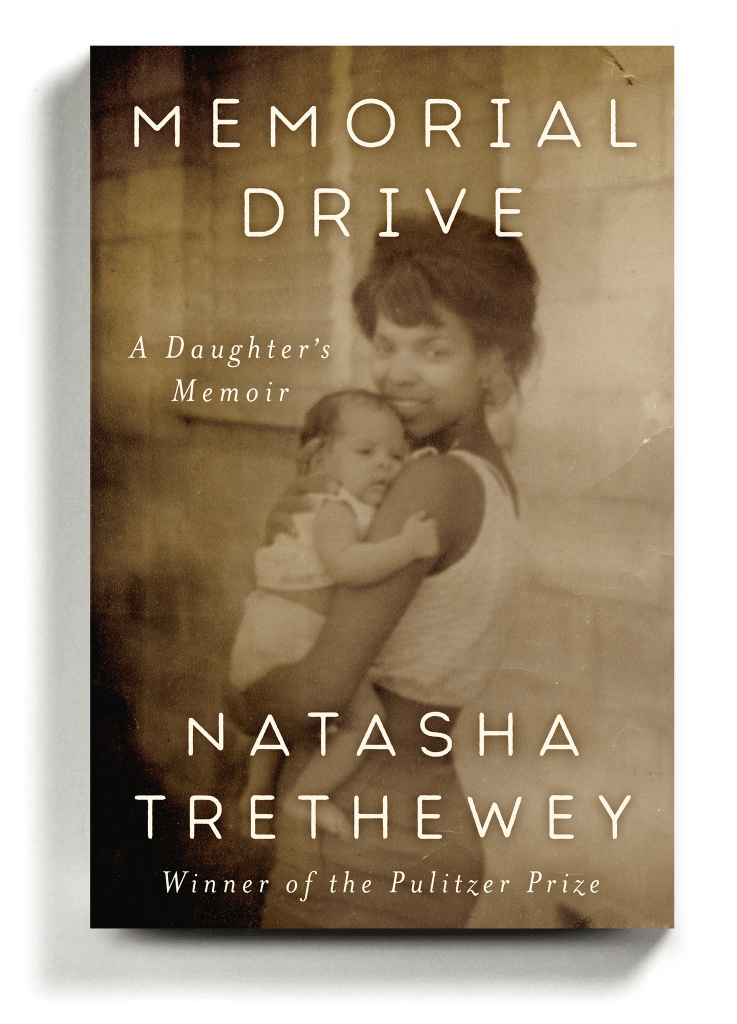

The first full novel they have read this semester is Trethewey’s Memorial Drive: A Daughter’s Memoir. Trethewey is a former Poet Laureate and Pulitzer prize winner in poetry. She also, at age 19, experienced the trauma of her mother’s murder by her step-father. Prior to section of the memoir when her mother meets Big Joe (the stepfather) we learn a good deal of the author’s family history. In particular we learn about the marriage between her mother (an African American woman) and her father (a white Canadian man) in Mississippi at a time when miscegenation was still illegal, and we also learn about her grandmother and extended family history in the Delta region of Mississippi. We learn about the value her family places on education. We learn about the community she spends her childhood in, and how that environment shaped her and her identity.

After she and her mother move to Atlanta, we see through her eyes what “white flight” looks like, and we see the resulting impact on schools. We also meet Big Joe, who will become her step father. If you have ever used or seen the Power and Control Wheel and the Cycle of Violence, you will recognize all of his behaviors and the relationship dynamics.

Throughout the author’s adolescence, we continue to see her protective factors, including the relationship between her and her mother. We also see the limitations of the legal and criminal justice system with response to survivors of intimate partner violence. There are likely other ways you could use this book in teaching, but these are just a few.

And, throughout, the author weaves in her memories of that time with her current reflections and processing on the trauma. She finds there is power in remembering rather than avoiding. As she says toward the end “Even my mother’s death is redeemed in the story of my calling, made meaningful rather than merely senseless. It is the story I tell myself to survive.”