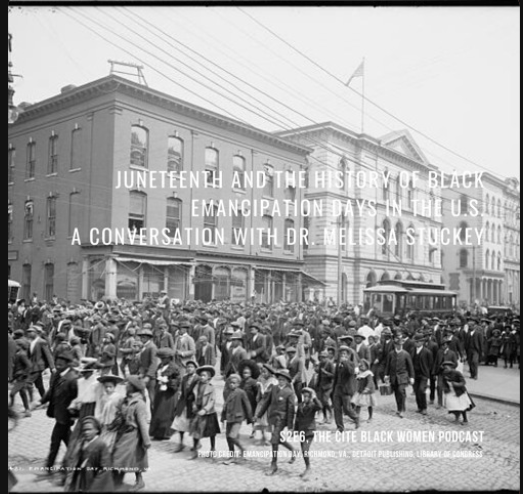

A couple of days ago (8/25) was the 100th anniversary of the first Black labor union, the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters. This is an example of a union that fought a long time to win increased wages and other rights, and is also a good example of co-occurring struggles for labor rights and civil rights more broadly. Seeing a reminder of this anniversary made me think a bit about other labor struggles that led to today’s progress…as well as the labor-related struggles we still face.

I always hope student have heard of Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta and their work with organizing farm workers, but if they haven’t, here is a helpful overview. There are also documentaries on their work and biographical films about each if you want a different genre to explore!

The Zinn Education Project also has great resources on teaching labor history, including lesser known organizers and people who were thrust into organizing because of their particular context…a great reminder that any of us could be/should be ready for “such a time as this”.

And, even though many of us enjoy Labor Day and all its traditions, there are so many worker rights issues in our country currently. Oxfam America says it simply and clearly: working poverty shouldn’t exist in one of the wealthiest countries in the world. This organization clearly outlines current worker rights issues in the US, an agenda for working families, and an interactive map on the crisis of low wages in the US. Oxfam also has a really informative interactive map/scorecard for the best and worst states for working women. As someone who teaches mostly women, this has been an interesting discussion starter in the past.

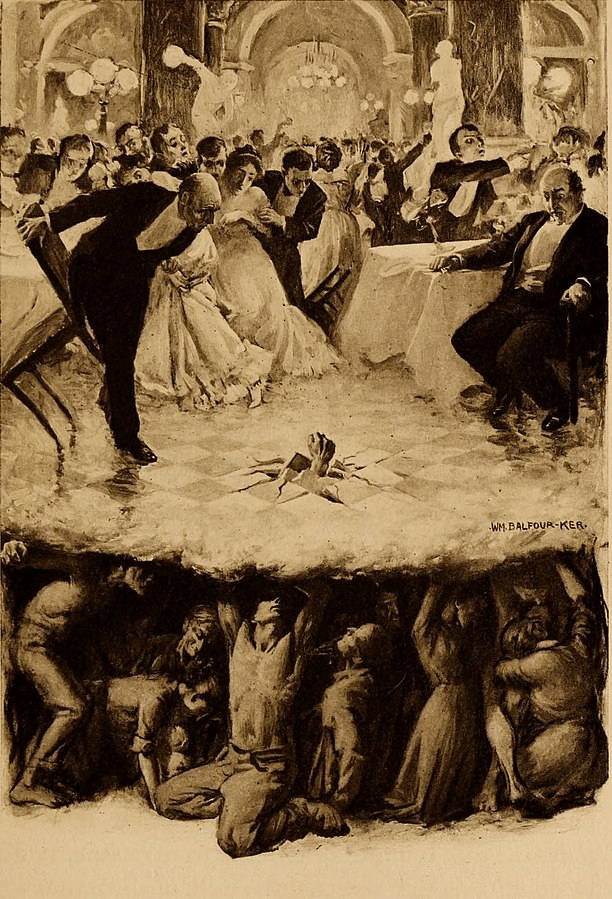

For several iterations of teaching a course on Poverty in the US, I used a book called A People’s History of Poverty in America. (Author is Stephen Pimpare). I stopped using it because I needed a newer book with more up to date statistics, but if you are looking for a book on the history of poverty in the US, this is a great one. Anyway, the picture below was on the cover of this book, and I always asked students to tell me what they were seeing. This illustration from William Balfour Ker is entitled “From the Depths”. Showing this picture and alongside data on income and wealth gaps could make for a very interesting labor-related discussion as well.

And for everyone who is a social work nerd and a history nerd combined (which might actually just be me!), you can also point someone in the direction of the 1937 presentation to the National Conference of Social Work on “Social Work and the Labor Movement”.

In all seriousness, though, I want my students to enjoy their day off from classes but I also want them to recognize the roots of labor day, and the labor struggles that still need people standing in solidarity.