Last night I was trying to settle down for sleep, which is always challenging the night before the semester starts. I was tossing and turning, and then it hit me: I was about to embark on my 20th year of full- time teaching.

Earlier yesterday I read a post by my friend David Hutchens, who specializes in helping companies and organizations tell their stories. He posted on his social media sites about it being time to abandon the hero’s journey. He said that while it is fascinating and deserves our attention, the best uses of the hero’s journey as a storytelling tool take 2 hours or more. He went on to say that storytelling is best done in micro narratives, and that “Those small moments can say everything about who we are, and why we are here.” That really resonated with me, and I tucked the post away in my brain to think about more at a later time.

That time came sooner than I expected, as I realized last night about it being a big anniversary for me in terms of teaching. I thought about how my pedagogy had shifted over the years in small ways, but honestly the things that were important to me then are what drive my teaching now. I want students to be able to experience community in class. I want them to be able to translate theory and other concepts into practice in order to work effectively with people. I want them to think critically and act with integrity. I want them to remember the importance of relationship.

I was a good teacher 20 years ago, and I am a good teacher now. It isn’t bragging to say that, when in the same breath I can tell you ways I fall short.

In terms of a hero’s journey: I will never win a big teaching award or be famous for my teaching. I won’t have an epic period of revelation or transformation. This isn’t my story.

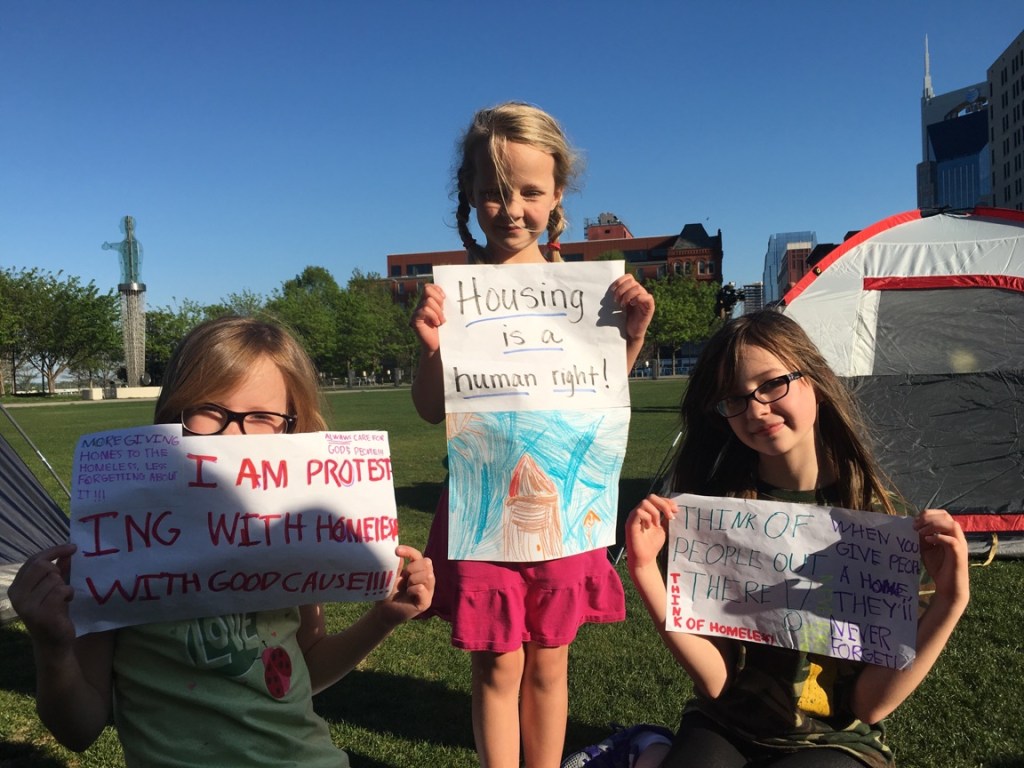

But I have about a million micro narratives, some of which have occurred in class and some of which have happened outside of class. I think about the night a student gave a spoken word about her fears that her brother, a biracial teen, would experience violence at the hands of police. I think about the same class the following week, where a student gave a spoken word about Blue Lives Matter. I think about the tension of having to hold space for both of those students, and to simultaneously support both students in the ways they needed while encouraging growth. I think about the days and nights students have shared part of their stories, and their family stories, as a way of making sense of who they are and what has called them into a profession of service and advocacy.

I think about the number of students who have come into my office over the past 19 years to tell me they had gotten engaged or eloped! I think about the number of people who have come to my office to tell me they were pregnant, and sometimes their parents didn’t yet know. (To the best of my memory there is no Venn diagram overlap in that group of people.) I think about the number of people I have walked over to student counseling services, knowing that they needed to be there but not wanting to send them out alone. We all need someone to come along with us in some times and spaces.

I think about the number of times a Marvel character has entered my classroom. Okay, so it is only one time but…..how many of you can say Spiderman appeared in your classroom? (Still unclear why this happened but it was fall of 2020 and who was really questioning anything?)

I like thinking of my teaching as an anti-hero’s journey. And I am thankful to my friend Dave for helping me see the value in remembering the micro stories. Not every class is going to be exciting or have a big win of some kind, but every day I teach there are moments where I can bring my best self (the one that exists in that moment, your mileage may vary from time to time) to students in order to listen deeply, to encourage them, and to meet them where they are in that moment. I get to help them think about things they may never have questioned before, like why poverty is so prevalent, and why aren’t we taught certain things in our typical history classes. I get to be in relationship with them as they are preparing to do good work in the world.

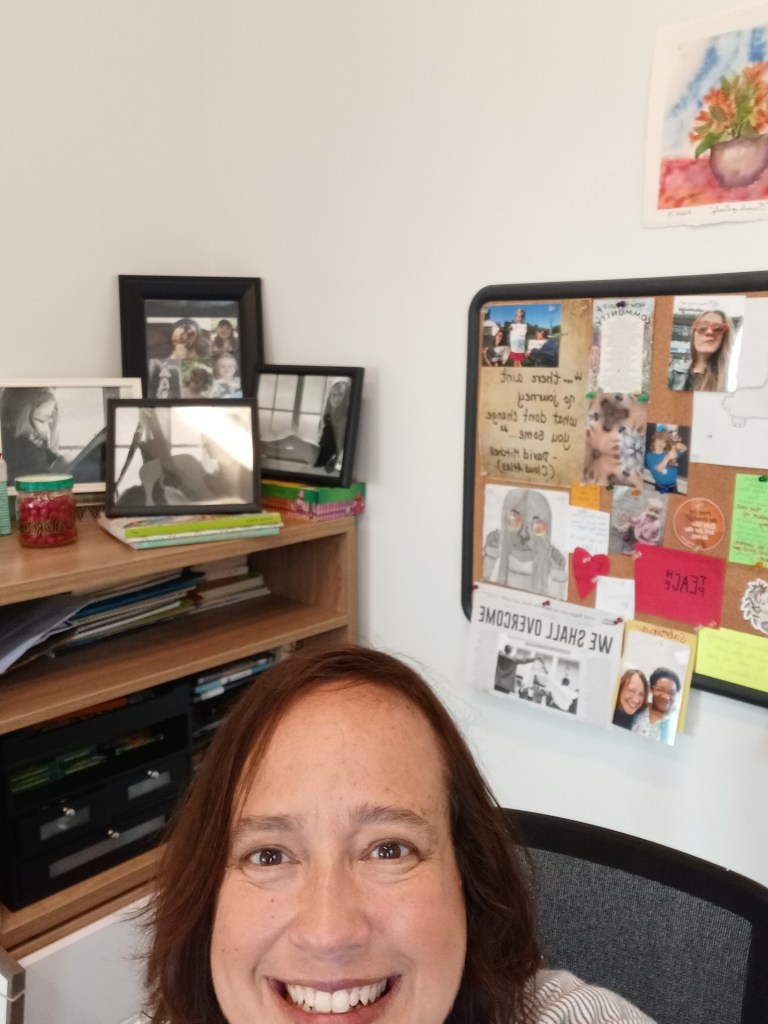

Today, before my first class, I took a picture of myself in my office, and then I happened to walk with a new colleague to our first classes and she asked for a pic of the two of us. In both pictures I am happy, and also hyped up on adrenaline and Coke (the legal kind bottled in Atlanta, not the other kind).

At the end of the day, I looked tired. Like really, really tired. Taylor Swift is right about this, as she is about many things: it is exhausting to always be rooting for the anti-hero. It is also exhausting to be one, especially in a semester with four different preps and my own children at developmentally significant stages.

But I promise to keep showing up. And whatever year of teaching (or community building or accounting or parenting or whatever) it is for you, I hope you have peace in remembering that there are scenes and moments in your work and your life that make a difference.

Embrace your anti-hero’s journey.